Building Test Pyramid to optimize automated testing

Tired of fragile tests that break without a reason? Full test run takes hours and you feel sick of endless test optimization? Waking up in the middle of the night screaming SELENIUM PLEASE NO? These are common symptoms of a wide-spread disease called Hypopyramidism. Traditional treatments are usually symptomatic: fine-tuning timeouts, running tests in parallel, taking anti-depressants and so on. But a real cure exists. And you've probably heard of it before. Its name is Test Pyramid and in this article we'll use it to make our tests fast and furious.

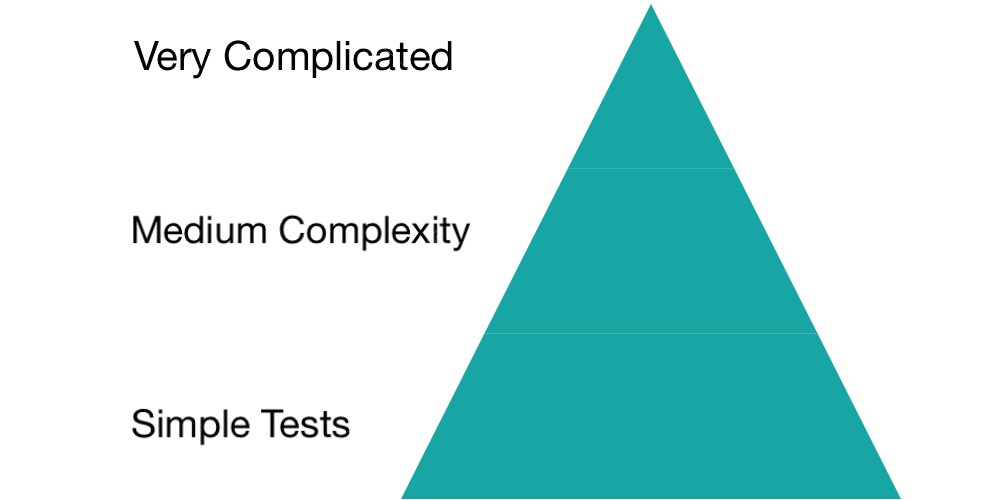

So what is a Test Pyramid?

Test Pyramid describes a simple idea that the more complex the tests are - the smaller number of them you should write. Traditionally every pyramid is drawn as a triangle hehe:

The layers correspond to Unit, Component and System tests. According to our terminology:

- Unit Tests concentrate on functions and classes. These are very simple, fast and stable.

- Component Tests check whether those classes, when joined together, do what was intended. They don't require full app being deployed. Often people call them Integration Tests. These tests are not as fast or simple as unit tests, but still are very stable.

- System Tests are run against fully deployed app. These are very complicated and slow tests. And they depend on both stability of the testing tools, the app under test and infrastructure. Every part can break and we may get a false-negative test run.

While a lot of people know this, in practice we have a totally different picture - a lot of unnecessary testing is done at System Level. I've seen a project where they ran their tests in 10 threads and the full run took 3 hours!

In a different project they had a well-known problem that they couldn't run all the tests without a failure. A glitch-like failure, not a real bug. They handled it in a very peculiar way - a threshold was introduced: if the number of failures were below the bar, they treated it as green. Very deterministic testing!

I myself had a chance to write tests in this way for some time. Ended up with the full run taking 5 hours. And that was after the optimizations - we were running a part of them in headless browser. Was it worth it? Let's say that it was a nice experience of how we shouldn't do.

But hey - let's break this vicious tendency. Keep reading and you'll see how we can change it for better.

Example of Test Pyramid (Groovy + AngularJS)

Are you ready to build a test pyramid? Note though that it depends a lot on the technologies we use in the app. The pyramid for your app will probably look very different! Below we'll consider a sample app which is called... Test Pyramid! It's written with AngularJS, Spring MVC and Hibernate which dictates a lot how the tests look. You can find both production and test sources at the BitBucket repo. Here we only will show a small set of those to illustrate what logic needs to be tested at what level.

Couple of words on the application we're going to test now: you can create pyramids with Name, N of System/Component/Unit tests and those pyramids are saved into DB. There is basic validation both on UI and on Back End. You can click on the pyramid in the list and it will be drawn for you.

Server Side Unit Tests

Here's a good candidate for Unit Testing, the only logic present is validation rules:

class Pyramid {

Long id

@NotNullSized(min = 1, max = 100)

String name

@Min(0L)

int nOfUnitTests

@Min(0L)

int nOfComponentTests

@Min(0L)

int nOfSystemTests

}The code is simple and we don't need to initialize a lot to test it. We use Spock here since validation is easier to test with data-driven tests at which Spock is very good. And we use Datagen to randomize test data:

class PyramidTest extends Specification {

@Unroll

def 'validation for name must pass if #valueDescription specified (#name)'() {

given:

Pyramid pyramid = Pyramid.random([name: name])

Set violations = validator().validate(pyramid)

expect:

pyramid && 0 == violations.size()

where:

name | valueDescription

randomAlphanumeric(1) | 'min boundary value'

from(2).to(99).alphanumeric() | 'typical happy path value'

randomAlphanumeric(100) | 'max boundary value'

from(1).to(99).numeric() | 'numbers only'

from(1).to(99).specialSymbols() | 'special symbols'

}It simply creates an object of class Pyramid, sets the name to whatever value is needed for the test and

checks that validation logic returns an empty set of violations. In this example we covered only positive

cases for name validation, see the project sources for other tests.

Every line of the where block will resolve in its own test case:

validation for name must pass if min boundary value specified (c)

validation for name must pass if typical happy path value specified (z8mMVw0nbUKKxCjsCgnJoBqG2JyF9Jcax8Gr69Y0ZElds1YKy)

validation for name must pass if max boundary value specified (lZ1M1yBMa0STfYbj6KntkI9mGlxlxhff2...)

validation for name must pass if numbers only specified (941525639352684027677613208)

validation for name must pass if special symbols specified ((§*:$'"'`[)Important Notes:

- Isn't that very different from what we often do in practice? Usually this is a System Test which takes 1000x more time to run.

- We invoked a Validator (this is a separate lib that implements Bean Validation spec) in the test itself, it doesn't mean that our app will invoke it and will treat the results correctly! Keep reading.

Server Side Database Tests

Traditionally a lot of projects have a separate layer for that. Terms differ (DAO - Data Access Object, DAL - Data Access Layer, Repository), but the general idea is the same - you've got separate set of classes responsible for work with DB:

class PyramidDao {

Pyramid save(Pyramid pyramid) {

session.save(pyramid);

return pyramid

}

List list() {

return session.createQuery('from Pyramid').list()

}

}This is handy since we can have separate set of tests that cover DB logic. In this case there is no data-driven tests, therefore we'll use Groovy JUnit to keep tests compact:

@ContextConfiguration(locations = 'classpath:/io/qala/pyramid/domain/app-context-service.groovy')

@Transactional(transactionManager = 'transactionManager')

@Rollback

@RunWith(SpringJUnit4ClassRunner)

class PyramidDaoTest {

@Test

void 'must be possible to retrieve the Pyramid from DB after it was saved'() {

Pyramid pyramid = dao.save(Pyramid.random())

dao.flush().clearCache()

assertReflectionEquals(pyramid, dao.list()[0])

}

@Test

void 'must treat SQL as string to eliminate SQL Injections'() {

Pyramid pyramid = dao.save(Pyramid.random([name: '\'" drop table']))

dao.flush().clearCache()

assertReflectionEquals(pyramid, dao.list()[0])

}

}Important Notes:

- We test SQL Injection at this level. Which is often done at System Level and is 100x times slower

- These are Component Tests since they require a large part of the app to be initialized

(note

@ContextConfiguration) - These are Component Tests since they require In-Memory DB to be initialized (like HSQLDB). It imitates the real DB. If needed these test can be run against the real DB as well.

Even though these are Component Tests, we consider and treat them separately since they are very special.

Server Side Component Tests

Every application has its entry points and in our case these are Spring MVC Controllers/REST Services.

Usually those are accessed when HTTP request hits the App Server which in turn passes it to the entry points.

But imagine if we could hit those entry points without HTTP - by directly invoking objects and their methods.

And that's what we're going to do now. Here are our entry points that handle /,

/pyramid and /pyramid/list URLs respectively:

@RequestMapping(value = '/', method = RequestMethod.GET)

ModelAndView index() {

return new ModelAndView('index', [savedPyramids: new JsonBuilder(pyramidService.pyramids()).toString()])

}

@RequestMapping(value = '/pyramid', method = RequestMethod.POST)

@ResponseBody

Pyramid save(@Valid @RequestBody Pyramid pyramid) {

pyramidService.save(pyramid)

return pyramid

}

@RequestMapping(value = '/pyramid/list', method = RequestMethod.GET)

@ResponseBody

List> pyramids() { return pyramidService.list() }Some of them simply generate an HTML page, others are REST services that operate with JSON representation

of Pyramid class. Different web frameworks (Spring MVC, RestEasy, Jersey, etc.) provide different frameworks

to test them. In our case it's MockMvc:

MvcResult result = mockMvc.perform(post('/pyramid')

.content(new JsonBuilder(pyramid).toPrettyString())

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)).andReturn()If we put this code directly into test it'll be overloaded with technical stuff and we'll hardy follow the

code, therefore it makes sense to encapsulate this logic into separate layer of your tests (in our case this

is a class Pyramids). After that the tests look clean and readable for most people:

@RunWith(SpringJUnit4ClassRunner)

@WebAppConfiguration

@ContextConfiguration(locations = [

'classpath:/io/qala/pyramid/domain/app-context-service.groovy',

'classpath:/spring-mvc-servlet.groovy',

'classpath:/app-context-component-tests.groovy'])

class PyramidComponentTest {

@Autowired Pyramids pyramids

@Test

void 'service must save a valid pyramid'() {

Pyramid pyramid = pyramids.create()

pyramids.assertPyramidExists(pyramid)

}

@Test(expected = MethodArgumentNotValidException)

void 'service must return errors if validation fails'() {

pyramids.create(Pyramid.random([name: '']))

}

} Interesting fact - on one of my projects there were a number of System Level tests that were running against REST services. We made it possible to run them both against services and using direct object invocation. And the timing for 800 tests run dropped from 9 mins to 2.

Important Notes:

- These tests initialize almost the whole app - starting from the entry points and ending up with DAO and In-Memory DB. But they don't require the Application Server and can be run along the Unit Tests!

- These tests allow you to get rid of mocking in unit tests. The problem with mocks - they interact with the internal logic of your classes and therefore will change every time that logic changes. Also, we often find ourselves in situation when we mock a lot and therefore we mostly test how we initialize our mocks rather than how our business logic works (remember those weird tests for Service Layer? BTW, where are the tests for the Service Layer? ;)). So mocks are evil, but sometimes are necessary. Component Tests will free us from unnecessary mocking.

- These tests check whether validation is invoked by production code. Note, that there are no massive checks of validation rules - that's left in the unit tests. Instead we violate only one rule (empty pyramid name) and check if that resulted in an error. That's it - we know the the rules are respected and the validation is invoked!

- Because all the communication with Controllers/REST services in this case is via JSON we also check Serialization/Deserialization.

Server Side System Tests

And we conclude our Server Side series with System Tests which check the REST Services:

@Test

void 'add pyramid should allow to successfully retrieve the pyramid'() {

def json = pyramid()

rest.post(path: '/pyramid', body: json.toString())

def expected = json.content

def pyramid = rest.get(path: '/pyramid/list').data.find { it.name == expected.name }

assert pyramid

assert pyramid.nOfUnitTests == expected.nOfUnitTests

assert pyramid.nOfComponentTests == expected.nOfComponentTests

assert pyramid.nOfSystemTests == expected.nOfSystemTests

}

@Test

void 'add invalid pyramid should result in validation errors'() {

def json = pyramid([name: ''])

Throwable error = shouldFail(HttpResponseException) {

rest.post(path: '/pyramid', body: json.toString())

}

assert error.message.contains('Bad Request')

} Important Notes:

- There are only couple of tests on that level - we need to do only the basic checks for every endpoint

- These kind of tests don't check the business logic - it was already checked. Here we test only the fact

that things like

web.xmlor App Server descriptor are written correctly.

UI Unit Tests

There is much more logic at UI. Let's have a look at the logic that calculates the percentage of every test level in the created pyramid:

function updateProportions() {

var sum = self.tests.reduce(function (prevValue, it) {

return prevValue + (+it.count || 0);

}, 0);

self.tests.forEach(function (it) {

it.proportion = sum ? it.count / sum : 0;

if (!it.count || isNaN(it.count)) {

it.label = '';

} else {

it.label = +(it.proportion * 100).toFixed(1) + '%';

}

});

return [self.unitTests.proportion, self.componentTests.proportion, self.systemTests.proportion];

} That looks tough - I know what's going on here only because I wrote it. When field self.tests

is updated it's used by UI to be shown as labels near inputs. If all input fields are empty, then

empty labels will be shown. If there are digits, then the sum will be calculated and the percentage of every

test type will be calculated.

Now, let's see couple of tests that cover this logic. They are written in Jasmine + Karma:

it('test percentage must be empty if sum is more than 0 and one of test counts is non-numeric', function () {

sut.currentPyramid.unitTests.count = moreThanZero();

sut.currentPyramid.componentTests.count = alphabetic();

sut.updatePercentage();

expect(sut.currentPyramid.unitTests.label).toBe('100%');

expect(sut.currentPyramid.componentTests.label).toBe('');

});

it('must set empty to other test percentages if only count for system tests was filled', function () {

sut.currentPyramid.systemTests.count = moreThanZero();

sut.updatePercentage();

expect(sut.currentPyramid.componentTests.label).toBe('');

expect(sut.currentPyramid.unitTests.label).toBe('');

});These tests check that the labels are updated to 100% or to empty values in cases the digits are entered or not.

Important Notes:

- Since this logic is algorithmic, it fits perfectly for unit testing. There may be so many of these cases - and therefore they will require so many tests. If we write them at System Level we'll quickly end up with runs that take hours.

- While we checked that our calculations are correct, how do we know that the UI really shows these values? This question will be answered next.

UI Component Tests

Prepare yourself since this will be the hardest part of the tests! With frameworks like AngularJS we have a lot of logic both in JS and HTML. While JS logic can be covered by unit tests, to test how this JS is triggered by HTML and how it impacts HTML we'll need to check fully functioning UI. So here is a piece of HTML which we'll cover:

Plenty of logic is present here:

- Only 8 symbols can be entered into the field

- Characters need to satisfy pattern

[0-9]+ - Input value is bound to fields of AngularJS Controller (

data-ng-model="testType.count") - When value of the input is changed, a function needs to be triggered:

data-ng-change="pyramid.updatePercentage()"

Phew! Too much is going in these couple of lines, isn't it? The tools to cover HTML pages are well known - Selenium + Protractor (the latter is a wrapper around WebdriverJS that targets AngularJS apps specifically). But if we test against a fully deployed app we're back to hours of test runs. So how do we speed them up? Here are the possibilities for improvements:

- Both tests, Selenium and the app need to be located on the same machine to eliminate network traffic between these components.

- Server Side needs to be fully mocked to get rid of application server and database. Besides pure page load optimization it will give the control over what we initialize in UI and will provide shortcuts to access deep parts of the UI (e.g. the page that we could see only when we're logged in).

So first of all before the tests start we instantiate a NodeJS server that serves static resources and handles AJAX queries:

app.use('/favicon.ico', express.static(path.join(self.webappDir, 'favicon.ico')));

app.use('/vendor', express.static(path.join(self.webappDir, 'vendor')));

app.use('/js', express.static(path.join(self.webappDir, 'js')));

app.use('/css', express.static(path.join(self.webappDir, 'css')));

app.get('/', function (req, res) {

res.render('index.html.vm', {savedPyramids: JSON.stringify(self.pyramids)});

});

app.post('/pyramid', function (req, res) {

var pyramid = Pyramid.fromJson(req.body);

self.addPyramid(pyramid);

res.status(200).json(pyramid);

}); And then we write the tests themselves that type into the inputs and observe the results:

it('unit tests field must be empty by default', function () {

homePage.clickCreate();

expect(homePage.getNumberOfTests('unitTests')).toBe('');

});

it('unit tests label must be updated as we type', function () {

homePage.clickCreate();

homePage.fillNumberOfTests('unitTests', 10);

expect(homePage.getLabel('unitTests')).toBe('100%');

});We omit Page Objects here to keep article shorter, you can find that code at BitBucket.

Many people would argue about the necessity of Server Side mock - won't we implement the back end logic twice? To be honest - I haven't tried this in real projects yet (though soon I will try it out), so take my reasoning with a grain of salt:

- The mock will be much easier than a real back end. It's like mocking in the unit tests - you have to write some logic there as well, don't you?

- UI Component Tests won't be failing because of the bugs from Server Side. And we really don't want that to happen since additional re-runs of these tests will take a lot of time.

- The real Server Side may not provide enough of flexibility to test variety of situations. These situations may not be possible from server side at the moment, but UI may still need to be tested with those.

- It will hardly be possible to install CI Agents and Selenium at the machines where the real app is deployed. Ergo, we cannot eliminate network communication. But NodeJS mock can be run along with the tests at the build machine (yeah, that build machine still would need Selenium and browsers).

- Again - with real Server Side you may need some data preparation and additional steps (to sign up, sign in, create some items) before you get to a place where you can test some of the UI functions. With mocks it's much easier.

- UI Development in general should be faster with those. Deployment is easier and much quicker. And if there is a nasty bug on the Back End, it doesn't block UI folks!

To sum up - since UI tests are so complicated and so costly it makes sense to work on their optimization. If you spend time implementing a mock you'll free yourself from constant problems with false-negatives which in turn takes time because you have to read reports, reproduce issues and re-run these tests.

Important Notes:

- These tests are concentrated on how UI behaves. They don't check calculations or server side communication.

- A run of these tests should be the longest among all of the tests in apps where a lot of logic is on UI. This is because there are many of the tests, but in the same time they need to be run in browses which is very slow.

- To keep tests simple and predictable you'll need to make HTML pages testable. For that you'll have to include IDs, names, custom attributes so that it's easy to bind to the elements. That'll pay off quickly.

UI System Tests

Finally! This is the last part of the tests we'll consider! And it will be short, here are the tests:

it('adds newly added item to the list of pyramids w/o page reload', function () {

var pyramid = homePage.createPyramid();

homePage.assertContainsPyramid(pyramid);

});

/** This is done by server side when page is generated. */

it('shows item to the list of pyramids after refresh', function () {

var pyramid = homePage.createPyramid();

homePage.open();

homePage.assertContainsPyramid(pyramid);

});

/** This is done by server side when page is generated. */

it('escapes HTML-relevant symbols in name after refresh', function() {

var pyramid = homePage.createPyramid(new Pyramid({name: '\'">'}));

homePage.open();

homePage.assertContainsPyramid(pyramid);

}); Important Notes:

- These tests are mostly concentrated on how UI collaborates with the Back End. They don't check the business logic (and therefore there are few of them), they don't check the UI (and therefore there are few of them).

- Since we've got our tests that check how UI works on lower level, we don't have to run UI System Tests in real browsers - we can run them in headless mode (HtmlUnit, PhantomJS).

- The same Page Objects and other test layers can be re-used between Component Tests and System Tests. Ergo, we don't duplicate - all the scaffolding was prepared on previous stages.

So let's sum up?

Tests must be fast and reliable. If they take hours and fail from time to time - people stop trusting them, people stop counting on them. You've done a good job if:

- Your tests give the feedback very fast before the author of a change switched to another task

- You don't re-run the tests after a failure to find out if it was a glitch

- Your tests don't use mocking libraries or their usage is very limited

- The number of System Tests is tiny comparing to others

Remember that your pyramid may look totally different from what you've seen in this article. If you don't have a lot of logic on UI you may not be able to write UI Component Tests since the page generation depends a lot on server side. If you have different technologies like Spring JDBC instead of a full-blown ORM then your DB Tests may be very different from the aforementioned. And the list can go on, so prepare to be creative, your pyramids will be unique!

Interesting literature on the topic

- Depth of Test by ThoughtWorks

- Just Say No to More End-to-End Tests by Google

- Automated Testing and the Test Pyramid - nice article about Cost/Benefits of automated testing and Gherkin/Behave testing in particular.

- Why Most Unit Testing is Waste - an interesting viewpoint on the pyramid - author suggest to get rid of the unit tests as they take more than they give.

Next Steps

- Anaemic Architecture - enemy of testing is about how your project's architecture should look in order to support Test Pyramid.

- Randomized Testing - What, Why, When? is about how to further simplify and speed up your tests as well improve the coverage.

- Evolution of Automation Test Engineer on how Selenium tests can evolve from ugly looking ones to the business-oriented cases with OOP applied.